Medieval peasant fashion was built for labor, weather, and long wear, relying mainly on wool and linen with simple cuts that could be repaired easily and worn in layers across the seasons.

Materials

Most peasants wore wool as the primary outer fabric because it was warm, durable, and broadly available in many grades, with the coarser, undyed qualities common among lower classes.

Linen and sometimes hemp served for chemises, shirts, and head coverings because they were breathable, quick to launder, and cooler in warm months.

Dyestuffs were limited by cost and access, so natural sheep tones, russet, and modest plant dyes dominated, with pricier colors restricted by law or expense.

Core garments

A knee‑length wool tunic or dress over a linen under‑tunic (chemise or shirt) formed the daily base for most adults in rural communities.

Men typically added braies and hose for the legs, while women layered a long kirtle or gown over the chemise for coverage and warmth.

Simple belts, aprons, and occasionally cloaks or mantles completed outfits, prioritizing function over display.

Workwear logic

Field and craft work demanded freedom of movement, weather protection, and garments easy to mend, so cuts stayed loose and seams uncomplicated.

A farmer’s practical set might include a coarse wool tunic or smock, closely‑fitting leg coverings, and seasonal swaps like thicker wool layers or sheepskin in winter.

Linen layers next to the skin helped with hygiene and comfort, while outer wool resisted rain and wear during daily labor.

Headwear and footwear

Common headwear included linen coifs, simple hoods, and straw hats for sun and weather, reflecting task and climate more than fashion cycles.

Shoes were typically leather turn‑shoes or simple boots, with repairs expected and soles replaced as needed to extend life.

In poor conditions, clogs or pattens helped lift the foot from mud, preserving leather against damp and rough ground.

Colors and dyes

Legal and economic forces pushed peasants toward undyed wool, browns, grays, and the inexpensive end of plant dyes, producing a muted palette in most villages.

Russet—browns from cheaper processes—appears in English regulations as a prescribed cloth and color range for lower rural ranks.

More saturated shades like deep reds and blacks were costlier, signaling wealth or reserved status where law or custom applied.

Sumptuary laws

European sumptuary law policed class appearance by restricting luxury fabrics, furs, jeweled trims, and sometimes even coat lengths, especially in England and Scotland.

English edicts in the 14th century limited fur and fine silk to higher ranks, steering farming folk toward cheaper woolens and plain finishes.

These rules reinforced hierarchies while also promoting local cloth and discouraging imported luxury, shaping what rural people could wear publicly.

Seasonal layering

Winter brought heavier wool tunics, cloaks, and sometimes sheepskin to guard against cold and rain, with hoods and mittens aiding exposure work.

Summer layers shifted to lighter linen smocks and shirts under thinner wool or simple sleeveless overdresses for cooler wear without sacrificing coverage.

Repairable seams and modular pieces meant garments could be adapted across seasons, conserving scarce household resources.

Regional notes

“Peasant” was a broad social and economic category, so details varied by region, climate, and local cloth trade, even as the wool‑linen system held across much of Europe.

Access to dyes and secondary fibers differed with local agriculture and markets, producing subtle color and texture differences between communities.

Local customs and parish expectations also influenced what was considered decent or work‑appropriate in public spaces.

Women’s dress

A woman’s linen chemise under a wool kirtle or gown was typical, with aprons for work and head coverings marking modesty and practicality.

Outer layers could add sleeveless surcotes or simple cloaks, with lacing or ties used for fit adjustments over time.

Household spinning and plain‑weave linen helped explain the prevalence of straightforward cuts and repeated silhouettes in rural wardrobes.

Men’s dress

Men’s sets commonly used a shirt and tunic over braies and hose, with belts for carrying tools and pouches.

For heavy labor, shorter tunic hems improved mobility, while cold weather added hoods, cloaks, or heavier wool.

Leg coverings varied from separate hose to simple trousers in some regions, always balancing movement and durability.

Finishes and fastenings

Fastenings were minimal and pragmatic, such as ties, points, and simple laces, since buttons and elaborate metalwork could be expensive or restricted.

Seams emphasized strength in stress points rather than ornate decoration, consistent with work demands and limited budgets.

Trim and embroidery were sparse for lower classes, with any decorative weaving more likely to be functional bindings.

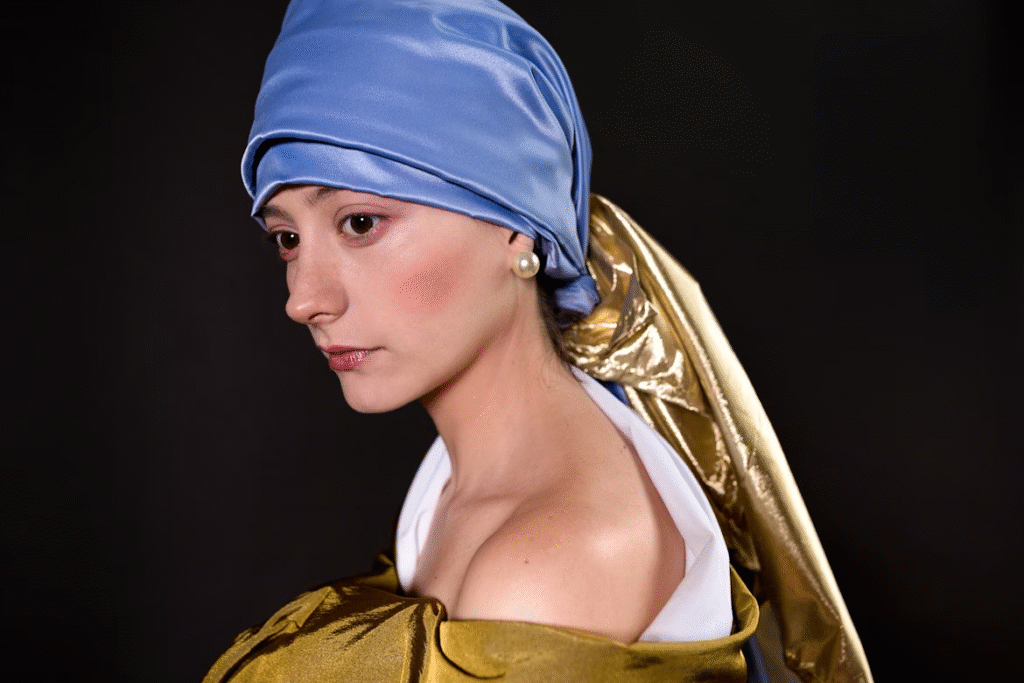

What “authentic” looks like (for makers)

Use undyed or naturally dyed wool for outer layers, plain linen for underlayers, and patterns that prioritize room for movement and straightforward repairs.

Build sets around a tunic or gown over a chemise, add a hood or coif, and choose simple leather turn‑shoes to align with rural contexts.

For color, stay near naturals and modest plant dyes, using brighter or luxury finishes only where a specific

context or higher status is documented.

Classroom or exhibit angles

Sumptuary law stories help audiences see how clothing enforced social order, trade policy, and morality in medieval Europe.

Fabrics tell economic history: wool quality tiers, linen as household labor, and dye costs that signal class boundaries.

Workwear design reveals rural realities—weather, tool use, and repair culture—making “fashion” a window into everyday survival.

Quick FAQ

- What did medieval peasants mostly wear day to day?

Layered wool tunics or gowns over linen shirts or chemises, with hose or simple trousers and pragmatic headwear and shoes. - Which fabrics were most common?

Wool for outer garments and linen for base layers, with hemp sometimes used for tougher work textiles. - Were bright colors common for peasants?

Generally no, because dyes were costly and many rich effects were restricted; natural tones and inexpensive plant dyes were typical. - Did laws control peasant dress?

Yes, sumptuary laws in places like England restricted luxury materials and trims to higher ranks, shaping what farming folk could wear.

2 thoughts on “Medieval Peasant Fashion: Practical Layers and Repairable Cuts”